This is Part 3 (of 3) of an essay discussing Hyper Realism is located, organised, constructed and applied within Titan A.E. (Bluth & Goldman, 2000).

Read Part 1 and 2 by following the link below…

Titan A.E. (2000) contextualised

How is Hyper Realism is located, organised, constructed and applied within Titan A.E. (2000). Part 1: Contextualising Titan A.E.

Realism and constructing belief in Titan A.E.

How is Hyper Realism is located, organised, constructed and applied within Titan A.E. (2000). Part 2: Paul Wells’ notes on Hyper Realism.

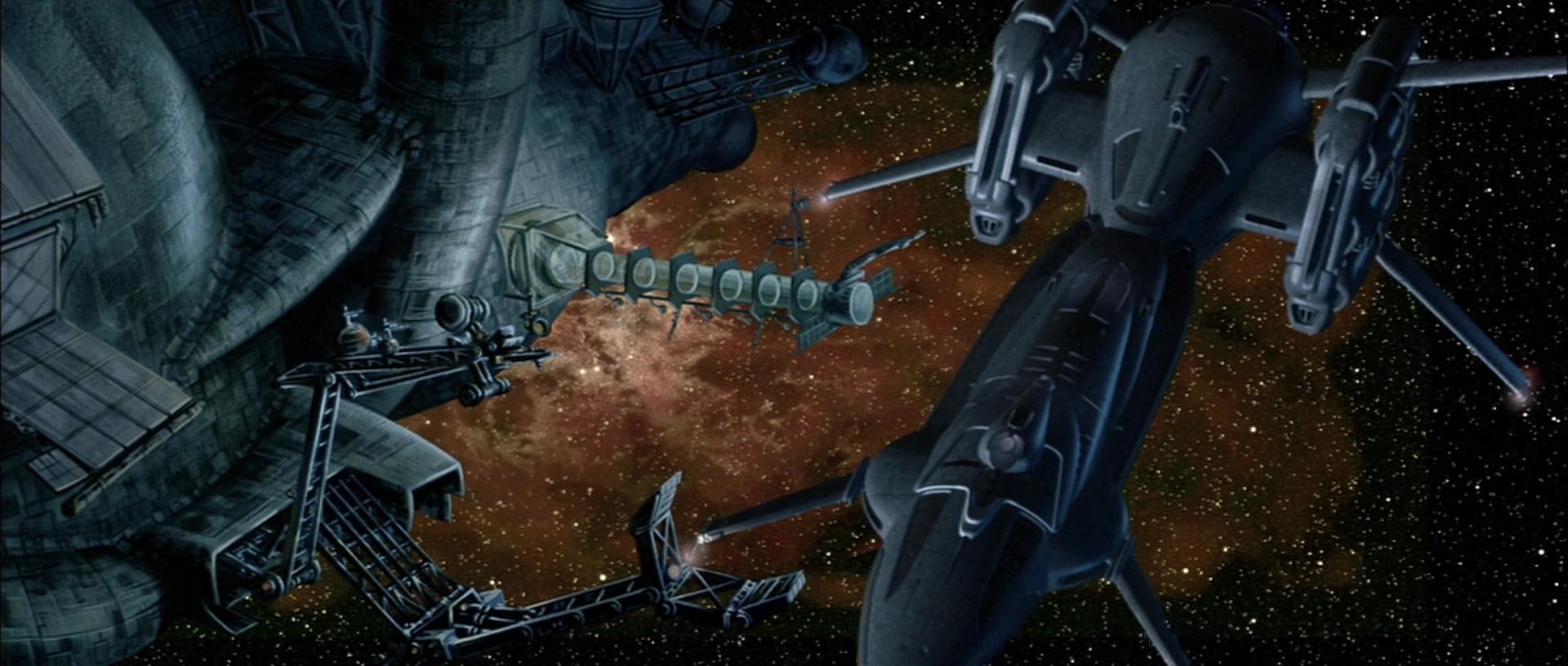

The enemies in Titan A.E are revealed to be pure energy, and they are 3D animated onto the 2D cel animation surrounding them. This unique way of portraying the enemy and the antagonist of Drej Queen Susquehana enables an extra layer of threat and an understanding that the danger to the heroes is “real”.

Wells notes how “Visual conversions echo those of live-action cinema in the ‘hyper-realist’ sense, deploying establishing shots, medium shots and close-ups etc., but camera movement tends to be limited to lateral left-to-right pans across the backgrounds or up-and-down tilts examining a character or environment.” (p. 37). This is not absolutely accurate for Titan A.E, as already discussed the camera movement has not always been simple left-to-right or up-and-down, however, establishing shots are present in the film and mimic those you would see in a live-action film. At the beginning of the ice crystal sequence, a close-up of Korso’s spaceship against a vast back-drop of space with overlayed text “ANDALI NEBULA – ICE RINGS OF TIGRIN” (1:01:27) before the spaceship changes course to head towards the nebula. This establishing shot is simple and introduces the sequence with little camera movement as Wells observes.

This is important for Titan A.E, especially with how the animation is switching between styles in the ice field sequence. The animation is presented in such a way it is easy to forget that it is an animation, providing a surreal or uncanny resemblance to what you would assume is reality – the reflections rippling in the ice, the fluidity of the “camera” following Korso through the ship, these all add up and aid in adding to the “realism”.

One issue remains with this analysis: How do you define what is real? Wells states:

Any definition of ‘reality’ is necessarily subjective. Any definition of ‘realism’ as it operates within any image-making practice is also open to interpretation. Certain traditions of film-making practice, however, have provided models by which it is possible to move towards some consensus of what is recognisably an authentic representation of reality. (1998, p. 24).

(Kuroyukihime, 2021)

For the definition to be subjective means what may be considered “real” by one person may not be by another. The camera movement through the spaceship following Korso may feel real as it goes against normal animation “rules” and provides a sense that you are there with the characters, but on the other hand how can it be real? It’s an animation of the interior of a spaceship, complete with artificial gravity – it is impossible to capture this in a live action form, as it does not exist. Each of the points I have discussed, be it the camera movement, or the reflections of the spaceship rippling across the ice crystals, aid in defining the “reality” of the animation. An audience knows it is not real, but that does not stop the animators trying to make it feel real.

In summary, Wells’ notes are relevant to Titan A.E., but certain segments of the film, including the ice field sequence, are far more experimental and start to drift away from his definitions and examples. Certain conventions seen throughout traditional cel-based animation are directly challenged within the sequence and in doing so provide an “uncanny” resemblance to what could be considered “real”. The distancing from the typical restraints of traditional cel-based animation and use of experimental three-dimensional animation enables the extra layer of realism to be experienced and aid in defining what an audience would consider to be “real”.

- Bluth, D. & Goldman, G. (Directors). (2000). Titan A.E. [Animation]. Twentieth Century Fox Animation; David Kirschner Productions; Fox Animation Studios.

- [Cale takes the helm]. (n.d.). Retrieved 20 January 2025, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120913/mediaviewer/rm502340609

- Freud, S. (2003). The Uncanny. Penguin Group. (Original work published 1919).

- Kuroyukihime. (2021, Dec 16). Titan A. E. – Titan builds New Earth 4K 60fps [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/dztwZfzYftk

- [The ship is reflected in the ice field]. (n.d.). Retrieved 20 January 2025, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120913/mediaviewer/rm66132993

- Wells, P. (1998). Understanding Animation. Routledge.

APA7

Cable, J. (2025, Feb 21). Realism and constructing belief in Titan A.E. (Continued). JCableMedia.com. [permalink].

Chicago

Cable, John. “Realism and constructing belief in Titan A.E. (Continued).” JCableMedia.com. February 21, 2025. [permalink].

Harvard

Cable, J. (2025). Realism and constructing belief in Titan A.E. (Continued). Available at: [permalink] (Accessed: 11 February 2026).