This post is a continuation of a series of posts investigating Henry Jenkins’ concepts of “Convergence Culture” and “Transmedia Storytelling”.

See the full series here.

Neil Perryman (2008) writes about how Doctor Who has used transmedia storytelling alongside new technology to drive the popularity of the Russell T. Davies era.

They outline how the BBC have used Doctor Who as a powerhouse behind what the BBC considers their “most successful attempt at turning a transmedia strategy into a successful and sustainable reality” (Thompson, 2007, as quoted in Perryman, 2008, p. 22). Perryman outlines Michael Grade’s speech about how “on-demand is coming and it will change everything” (Grade, 2006, as quoted in Perryman, 2008, p. 21), but note that a technical revolution is “not the endpoint for media convergence” (p. 21), suggesting that a story can be told using a new form of technology, but should not rely on that technology for longevity.

They also quote Jana Bennet saying “How and where we can watch comedy, drama and entertainment have undergone a revolution. The programmes themselves have not” (Bennet, 2004, as quoted in Perryman, 2008, p. 22), which is interesting when comparing this statement to Doctor Who, especially when investigating the different forms of media the storytellers have used to allow audiences to remain connected to the narrative.

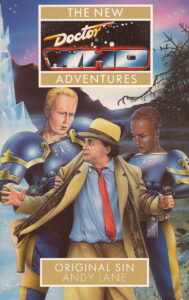

These stories “sometimes [provided] extra scenes and information that could not be gleaned from the episodes themselves, while occasionally correcting factual or narrative errors that had crept into the original television text” (p. 22), but these definitions became blurred due to the “little or no collaboration [existing] between the BBC and the books’ publishers”, often leading to “contradictions and surreal interpretations of the show’s protagonist” (p. 23). Paul Booth points out that this is not necessarily something negative, as “[the authors] built up a fanbase for Doctor Who that, importantly, demonstrated a willingness and a desire to participate with alternate versions of the story” (2018, p. 284), but resulting in “Doctor Who’s texts [existing] in a nebulous realm between canon and non-canon” (p. 295).

Overall, Perryman forms a strong outline of the different ways in which Doctor Who has used transmedia storytelling which allows an analysis into the BBC Disney partnership, and predictions for creative decisions moving forward. They conclude that “Doctor Who is a franchise that has actively embraced both the technical and cultural shifts associated with media convergence since it returned to our television screens in 2005” (p. 36), which is important as it suggests that they will continue to make these decisions as Doctor Who develops.

- Booth, P. (2018). Transmedia Fandom and Participation. The Nuances and Contours of Fannish Participation. In M. Freeman, & R. R. Gambarato (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Transmedia Studies. 279-288. Routledge.

- Lane, A. (1995). Original Sin. Virgin Books.

- [Original Sin (Lane, 1995) cover]. (n.d.). Retrieved 28 January 2025, from https://images.app.goo.gl/si5tGxmQWZtEujqw9

- Perryman, N. (2008). Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media. The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14(1), 21-39.

- [Virgin Publishing Doctor Who Novels]. (n.d.). Retrieved 28 January 2025, from https://i.imgur.com/rOUGMJb.jpeg

APA7

Cable, J. (2025, Apr 15). Perryman – Literature Overview. JCableMedia.com. [permalink].

Chicago

Cable, John. “Perryman – Literature Overview.” JCableMedia.com. April 15, 2025. [permalink].

Harvard

Cable, J. (2025). Perryman – Literature Overview. Available at: [permalink] (Accessed: 11 February 2026).